Hi Friends of Colorado's Rivers, A few months ago we decided to ratchet up our…

Part One: Is Trying to Save Lake Powell a type of ‘Climate Denial’?

Over the last few months, a lively discussion has erupted around the Colorado River basin about the use of, and fate of, Lake Powell.

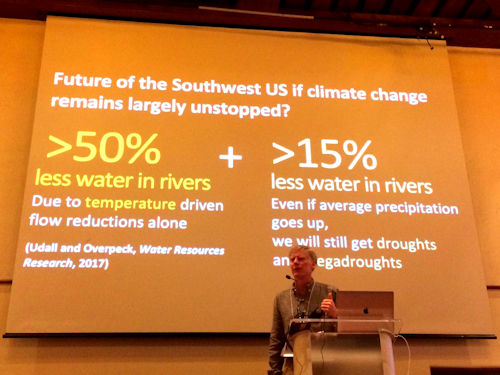

First, back on January 4, 2018, we posted a blog titled, “In 2018, the Colorado River Basin Needs to Embrace ‘Climate Change’ Not ‘Drought‘”. Two months later, the Colorado River Research Group posted a blog titled, “When Is Drought Not A Drought? Drought, Aridification, And The ‘New Normal'”. The sentiment of both posts is that everyone working in the Colorado  River basin needs to recognize that climate change is real, it has already caused decreases in flows and water availability in the Colorado River, and its going to get worse, likely much worse.

River basin needs to recognize that climate change is real, it has already caused decreases in flows and water availability in the Colorado River, and its going to get worse, likely much worse.

Our Jan. 4th post highlighted scientific articles arguing:

- that the best available science indicates that part of the cause of the lower flows that already have occurred in the Colorado River has been due to climate change,

- the best available science indicates that climate change impacts on flows in the Colorado River will increase over time, causing even less water to be in the river.

Our blog ended with this sentence, “Further, it has implications for the ‘Drought Contingency Planning’, which inaccurately acts as if the problem is temporary and will get better, while the best available science says that the problem is permanent and will get worse.”

Second, since that time, the “Drought Contingency Planning” as well as the controversy over Lake Powell has escalated. Two weeks ago, so-called “Dust Up” occurred on the Colorado River when the Central Arizona Project (CAP) posted a graphic indicating that they may try to take more water out of Lake Powell than they may be entitled to. Afterwards, there was well over a dozen responses from agencies and bloggers chastising CAP for its alleged actions. And then last week, the “West Slope Roundtables” in the State of Colorado had a meeting discussing the fate of Lake Powell, and whether to try to put more water in the Lake and save it as a “water bank”, or whether to abandon the Lake in favor or other locations for reservoirs or no new reservoirs at all.

The two items above are intricately connected.

The discussion, and presentations, at the West Slope Roundtable make it clear that the possibility of Lake Powell draining is real. Further, the graphs shown in these presentations indicate that the Upper Colorado River Basin water managers are preparing to drain the Upper Basin Reservoirs — Navajo, Blue Mesa, and Flaming Gorge — down into Lake Powell as climate change intensifies. And then, when more water is needed — perhaps “1 – 2 million acre feet” — they plan to use what they call “demand management” to run even more water down into Lake Powell. This so-called “demand management” involves buying water from farmers in Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming and legally forcing that water to go downstream into Lake Powell to prop up the Lake.

The “Upper Basin Drought Contingency Planning” has already toyed with buying water from farmers. Over the last three years, the federal government and water agencies have paid farmers to not divert an average of 7,000 acre feet/year. The “Drought Contingency Plan” hopes to ramp that up to 250,000 acre feet over time, though it may need as much as 1 – 2 million acre feet.

Let’s do some simple back-of-the-envelope math to see how much farm ground would have to be dried up in Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming to make this scheme work.

Farming in the Upper Basin uses an average of 32″ of water per acre to grow crops — corn needs a little more water, alfalfa needs a little less. Across the Upper Basin, rainfall averages around 14″ per year. So, on average, about 18″ of additional irrigated water is needed per acre to grow crops in the 3-state Upper Basin area, which is 1.5 feet of water per acre.

To get 7,000 acre feet of water, the federal government and water managers would have to pay farmers to not farm on ~4,666 acres of land. (7,000/1.5 = 4,666)

To get 250,000 acre feet of water, the federal government and water managers would need to pay farmers to not farm 166,666 acres of land. (250,000/1.5 = 166,666)

To get a middle point of predicted need of 1.5 million acre feet of water, the federal government and water managers would need to pay farmers to not farm 1 million acres of land. (1,500,000/1.5 = 1,000,000)

We ask this: Is it even remotely politically and financially realistic that farmers in the Upper Basin are going to stop farming and sell enough water to dry up 166,666 acres of land? And then, is there any way in the world that farmers would agree to stop farming and sell enough water to dry up 1 million acres of land?

Keep this in mind: In part of the Upper Basin in Colorado, the price of water hit an all-time high in 2017, at $31,000/acre-foot. So, potentially, if you had to buy 100,000 acre feet of water, it could cost $3.1 billion. One million acre feet of water could cost $31 billion. It’s true that hundreds of thousands of acre feet of water have been bought from farmers by cities over the last 4 decades across the entire Colorado River basin, but that water was bought by city ratepayers who wanted to use it, not by the federal government for the purposes of literally not using it, as would be the case with Lake Powell. Would the farmers sell their water to a government agency? Would U.S. taxpayers, or ratepayers in the Upper Basin, pay the price in order to not use the water?

The likelihood of Lake Powell draining is inevitable. Further — and tying it all together — as we noted in our Jan. 4th blog, and as

affirmed by the Colorado River Research Group blog in March, this is not a temporary situation. It is not “drought”; it is permanent “aridification”, and so the water can’t be temporarily leased. The water must be permanently bought and the land forever dried up, all in order to try and save Lake Powell.

We ask the provocative question: Is trying to save Lake Powell a type of ‘Climate Denial’? It does not seem that the federal government or the water managers are approaching the problem realistically. The political and financial reality of trying to buy hundreds of thousands of acre feet of water and drying up hundreds of thousands of acres of farms, or more, just in order to save Lake Powell, indicates that water managers may not be proposing a realistic solution to the escalating and inevitable problem of Lake Powell.

As we’ve said now dozens of times: The Lake is Mistake we must Forsake. We should save water, save money, and save farms by draining Lake Powell and tearing down Glen Canyon Dam, as soon as possible.

****

(Stay tuned for the Second and Third Part of the Lake Powell series.)